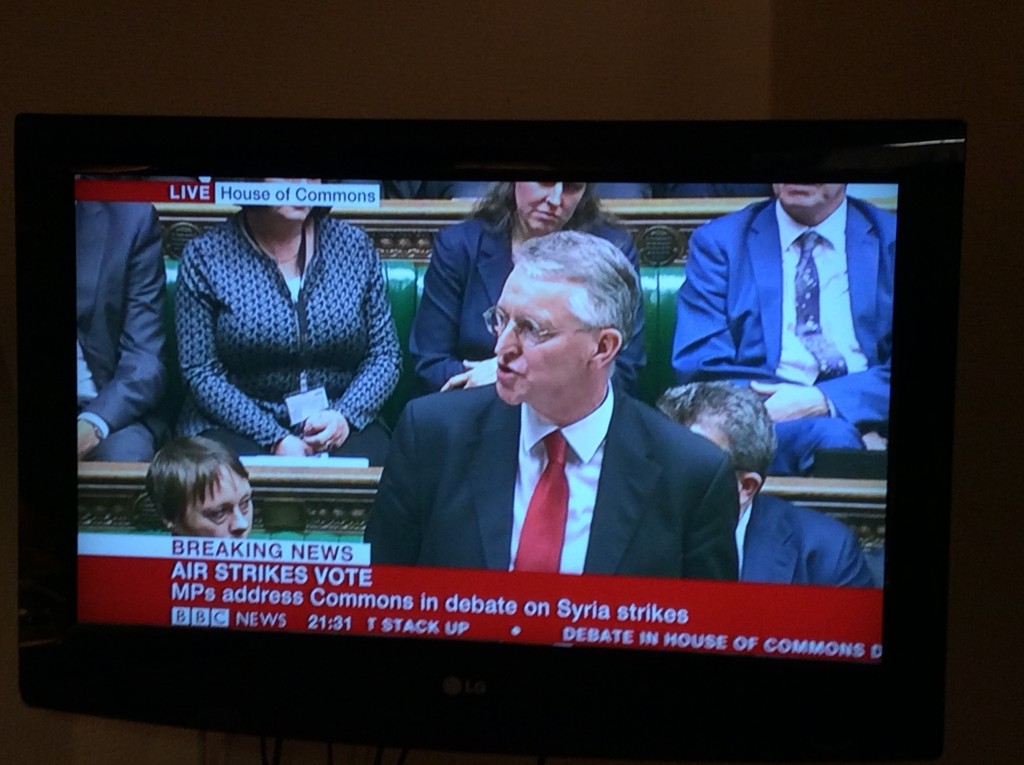

The Parliamentary debate on bombing IS/Daesh in Syria was brought to an intense and rousing conclusion by Hilary Benn, Shadow Foreign Secretary. It was Benn rather than Tory Foreign Secretary Phillip Hammond who inspired the House of Commons — MPs endured Hammond and applauded Hilary Benn.

The commentariat relished the difference between Hilary Benn and the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, but also inevitably, perhaps, with his father Tony Benn.

It was as if they had not noticed Hilary Benn’s eloquent defence of his leader — as a politician and as a person — and his unrequited invitation to David Cameron to apologise for his ‘terrorist sympathiser’ slur.

And it as if they had not noticed that throughout Hilary Benn’s parliamentary life he has not been an echo of his father — that the Benn family has survived generational and individual differences with better manners than most.

Melissa Benn — the only girl among Tony and Caroline Benn’s children, an astute writer and activist — reminds us that ‘the Benns have something of a history of courteous exchange but also of opinions strongly held to and expressed. Often not exciting enough for rapacious press, looking for gossip, intrigue and networking and power plays.

She’s right: schism and ‘irreconcilable differences’ attract attention, whilst respectful, intelligent and peaceful co-existence doesn’t.

Hilary Benn is not his father.

This is not a dynastic drama; it isn’t a sectarian schism either.

Hilary Benn has always disagreed with Tony Benn and with Jeremy Corbyn about Britain’s wars.

That makes Benn’s appointment as Foreign Secretary by Corbyn a daring move; just as his appointment of Maria Eagle as shadow Defence Secretary is also interesting. They don’t agree on the war in Syria. They don’t agree on the renewal of Trident nuclear missiles.

So, they’re going to have to work it out.

The surprise is that they’re going to try. And they’re going to try in the knowledge that these issues are difficult because they are difficult, we should expect disagreement because they are among the most testing themes of our times.

Listening to the Syria debate and Benn, brought to mind not his father but Parliament itself and a sense that Benn was emancipated by the context — Parliamentary democracy at work.

I didn’t agree with him about the bombing. But Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell, who has brought a genial tone to the Corbyn team, lost his touch a bit when he said Benn’s speech was like Tony Blair in 2003 when he argued for war in Iraq.

No, he wasn’t.

Benn wasn’t so much charismatic as effective: the performance was adroit, supple and smart. He didn’t overwhelm the honourable members with evangelism, he didn’t deceive or bully. He invited them to think, and to be available for persuasion. That’s what made his speech bracing.

Unlike, for example, David Cameron who de-humanised the enemy, Benn discussed some particulars — acts of violence animated by a special kind of manly excitement; an enemy that electrified by violence that is also thought-about and strategic: aimed not only at destruction but the theatre of terror.

That’s what made his allusion to fascism so interesting. Who knows if he’s right, but the word takes us to other modern — not medieval — ideologies of supremacist violence: the Nazis, Mussolini’s nationalism, racist lynching in the United States.

If he soared on this occasion it was because the occasion — the place, the time, the people — demanded it: here was Parliamentary debate at its best, and here was Hilary Benn doing his best.

Weirdly, the commentariat responded not by thinking, but by boxing the speech into its own discourses about power and politics. They’re missing the point: this isn’t about splits (whatever the ‘traitor’ twitters outside Parliament get up to).

Isn’t disagreement and debate what happens in political parties, in relationships, in families?

Westminster’s political culture isn’t used to this — witness the utter bewilderment about Scotland’s great independence conversation: households, friends, lovers dissented from each other — but they didn’t get divorced or die. They kept talking.

This is good politics, and Westminster and the commentariat should get used to it.

What we witnessed during the Syria debate was a party that was functioning; recovering from near death, from being eviscerated, hollowed out; from being ruled by diktat, by people whose anti-party politicking left Labourism too terrified to do what it is supposed to do: think, look right, look left, look right again and then go.